Of the many relatives I came to know in my research, one of my favorites was Margaret (Helm) Stone. Dad also loved her older cousin, I think, because, like my father, she was a straight shooter. She told you just what she thought. I loved her because of the spunk she showed throughout her life and her continued independence long into her 90s.

Of the many relatives I came to know in my research, one of my favorites was Margaret (Helm) Stone. Dad also loved her older cousin, I think, because, like my father, she was a straight shooter. She told you just what she thought. I loved her because of the spunk she showed throughout her life and her continued independence long into her 90s.

She was already close to 90 the first time I visited her at her small cottage in Venice, Los Angeles in 1996. The cottage had a charming garden that she carefully tended and which backed up onto one of Venice’s canals. The house was built at the turn of the century when Venice had been a resort area. Monte bought it in the 1950s when the area had hit hard times.

“I bought this house because it was cheap, but I love it.” She had previously lived in a nice house in Beverly Glenn that she bought when her father died in 1933 leaving her a good inheritance.

Then she married Leonard Stone, a handsome alcoholic who had three daughters from a previous marriage. The previous marriage had suffered, in part, because both Stone and his wife were alcoholics, according to Robert Patterson, Stone’s grandson.

Stone came from wealthy parents. His father had been a stockbroker in Australia working with a brother who was a partner in the same law firm as Herbert Hoover. The two were partners in several mining investments. Stone later move to California and became a mining engineer and the editor of a mining journal. He would short the stock of a mining company than write negative stories about the mine to drive its stock price down so he could buy the share back at a nice profit. Stone’s mother was also from a rich family. Her forebears had been the beneficiaries of a Spanish land grant. Her aunt had been one of the founders of Santa Monica. When Stone’s father ran away, perhaps after his unscrupulous activity was uncovered, Stone’s mother married a shipping magnate and inherited his money when he died a few years later.

So one images that Leonard Stone, the son, must have inherited a fair amount of money. Perhaps some of the money was lost in the 1929 crash. Perhaps he spent it all. In any case, he must have run out of money because in 1932 he was convicted for counterfeiting and spent 18 months in a penitentiary.

Monte probably knew nothing of that history. She remembered Leonard as an idealistic salesman with dreams and lots of ideas that never came to fruition. “He was ahead of his time,” she used to say pointing out that he was the first to come up with the idea of selling cut flowers in the supermarket. “He liked to bend the elbow,” she added, referring to his love for drink. Stone proceeded to spend all of Monte’s substantial inheritance on his various business ideas.

Fortunately, Monte still owned shares of Helm Brothers, which weren’t easy to sell. The couple lived on the $250 a month in dividends from Helm Brothers. But those dividends stopped flowing when World War II began. Leonard drank more and his health declined. In 1945 the doctor suggested Monte and her husband go to the desert to improve Leonard’s health. A friend got them jobs in Furnace Creek Valley. For nine months, Monte cooked for farm workers while Leonard put in irrigation lines for the date palms.

When they returned to Los Angeles in 1946, there was no place to live. Everybody was coming back from the war and housing was in short supply. She paid some money under the table and got an apartment for $100 a month. Sometime later, perhaps when the war ended and dividends started flowing again from Helm Brothers, Monte and Leonard moved into the Venice house.

The Venice house had a galley kitchen, a tiny living room and two small bedrooms. The first time I met her, I told her she had been one of my Dad’s favorite cousins. She smiled, then said in a husky voice that must have been sexy when she was young: “I remember going to Japan for a Helm Brothers board meeting. People were unhappy because your Dad was competing with Helm Brothers. We threw him out on his ass,” she said. Dad had started a competing company after his uncle had fired him as head of the company. The family had retaliated by removing Dad from the Helm Brothers board. But I could tell that Monte loved my father.

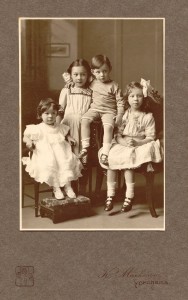

Monte served me tea and cookies, and we sat on the couch and talked as we went through pictures. She had lived a privileged existence as a young girl. She grew up in the Victorian mansion in Yokohama that my great grandfather built in 1902. She attended a French convent in Tokyo. Among her classmates was the Siamese ambassador to Japan.

She remembers her Japanese grandmother’s sister had given all the children gold bracelets. Her house burned down in the great earthquake of 1923 and her father built a grand new house in Hachiojiyama (Helm Hill) near Honmoku.

She remembers her Japanese grandmother’s sister had given all the children gold bracelets. Her house burned down in the great earthquake of 1923 and her father built a grand new house in Hachiojiyama (Helm Hill) near Honmoku.

When Monte first moved to Los Angeles in the 1920s, she lived with her aunt. Her aunt would call her “yellow” and make Monte stay in her room when guests came because she was embarrassed about having a Japanese relative. Her grandmother was Japanese.

Her father, Charles, had taken Japanese citizenship so that Helm Brothers ships could be registered in his name. It took years for Monte to get U.S. citizenship because of the 1924 Exclusion Act which prohibited those of Japanese heritage from getting citizenship. It was only because her mother was white and born American that she was able to get the papers. Monte’s parents were first cousins. Her mother’s father, Gustav, was the brother of her father’s father, Julius. When she finally got U.S. citizenship on June 13 1930, the Evening Herald wrote: “International girl becomes American.”

Not long afterward, Monte had trouble finding a job In the midst of the Great Depression, and she returned to Yokohama taking a second class berth on an NYK ship to save money. When the purser saw her name on the list he said; “Miss Helm, you mustn’t go second class. Your father will be very upset. I’ll put you in first class and your father will pay me back later.”

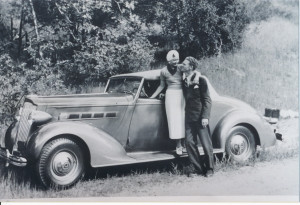

On the ship Margaret met Hayward Hunter of San Francisco, a young lumber salesman, and quickly fell for him. They spent time together in Yokohama and later Kobe. One evening, they were taking a taxi to Monte’s Uncle Jim and Aunt Elizabeth’s house in Maiko when the taxi stalled right on the train tracks. The driver was trying to restart the car when Margaret saw the lights of the train coming around the bend. The train rammed into the car knocking it on its side and pushing it up onto the train platform. The top of the car was ripped off. Margaret fell unconscious. They were lucky to be alive.

When Monte had recuperated, she and Hayward took the boat to Yokohama. Monte got off the ship at Yokohama to visit her family. Hayward stayed on the ship to go to San Francisco. She gave him a package to give to her Aunt Betsy in Los Angeles and wrote to her Aunt to meet the ship. She dreamed of marriage to Hayward. Her Aunt Betsy later wrote Monte that when she delivered the package to Hayward, he was there with his wife, who had come to take him home.

Monte could have lived an easy life if she had stayed in Yokohama. But she said she hated the way the foreign wives would hang out at the club and play mahjong all day long. She wanted to be independent. That was why she traveled to Los Angeles and went to secretary school. She was one of the few Helms I knew of her generation who worked most of her life. She couldn’t afford to retire early as most of her cousins had done.

She never felt bitter about the money Leonard had spent. She never felt she ever wanted more than that house in Venice. It had never been remodeled and looked much like it must have looked when it was first built at the turn of the century. Toward the end, she could have sold the house and lived comfortably in a retirement home. Yet she continued to live there taking a bus to do her grocery shopping, and in the end, wearing an oxygen mask as she did the house cleaning.

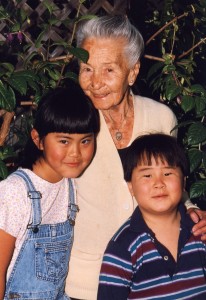

In the years that followed, I often visited her in Venice. The last time I went with my children. She was so pleased to see them. Before we left, we went out back into the garden she loved so much and I took a picture of her with Eric and Mariko. It is a reminder of one of the many special moments I had connecting to special people in the course of researching my book.

What a precious story!

Thanks Leslie. She was one of my favorite aunts. Didn’t mince words that’s for sure. Even after moving to Tuolumne from Santa Monica we still would see her quite often. All our kids loved her to; in fact, as she didn’t have any children of her own t think she knew more about her various and many distant cousins (“nieces and nephews” of the next generation) than anyone else.