I had long heard stories about a shipbuilding site in Yokohama where Helm Brothers, my family’s stevedoring company, used to build its barges and tugboats. A former company employee once told me how my grandfather, Julius Helm, would go with the company carpenter to the nearby woods on their horse cart to pick out trees for the lumber they needed to build the boats.

Then some years ago, Toshiko, my father’s second wife, who lives near Negishi station in Yokohama, sent me a clipping about a sign that had been posted on a bridge to mark the location of Helm Dock, the Helm Brothers’ shipbuilding operation. The story didn’t say where the bridge was so I never bothered to follow up.

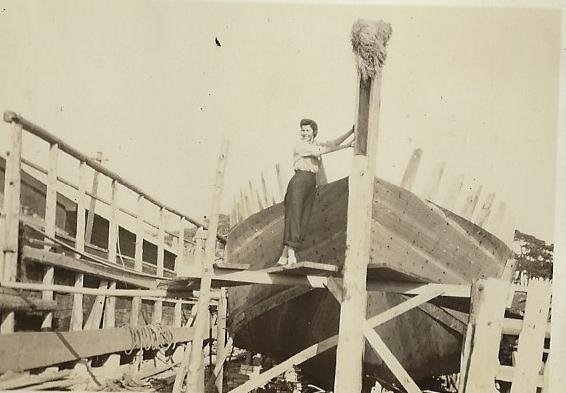

One day, as I was going through some pictures my Uncle Ray had taken in the early 1950s when he had been stationed with the U.S. Army in South Korea and had visited my parents in Yokohama. There was a picture of my mother standing on a barge. I had long assumed my mother must have visited a shipyard somewhere.

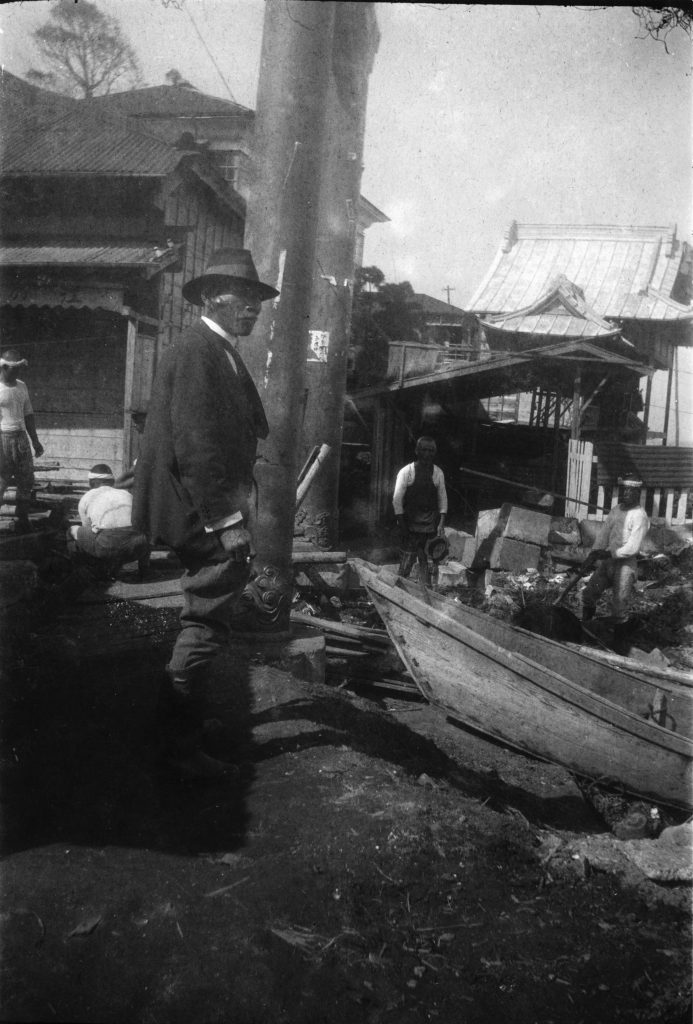

But then I came across another picture. This one showed my grandfather watching on as a barge was under construction. This must have been Helm Dock!

Grandfather Julius (aka Julie) at Helm Dock

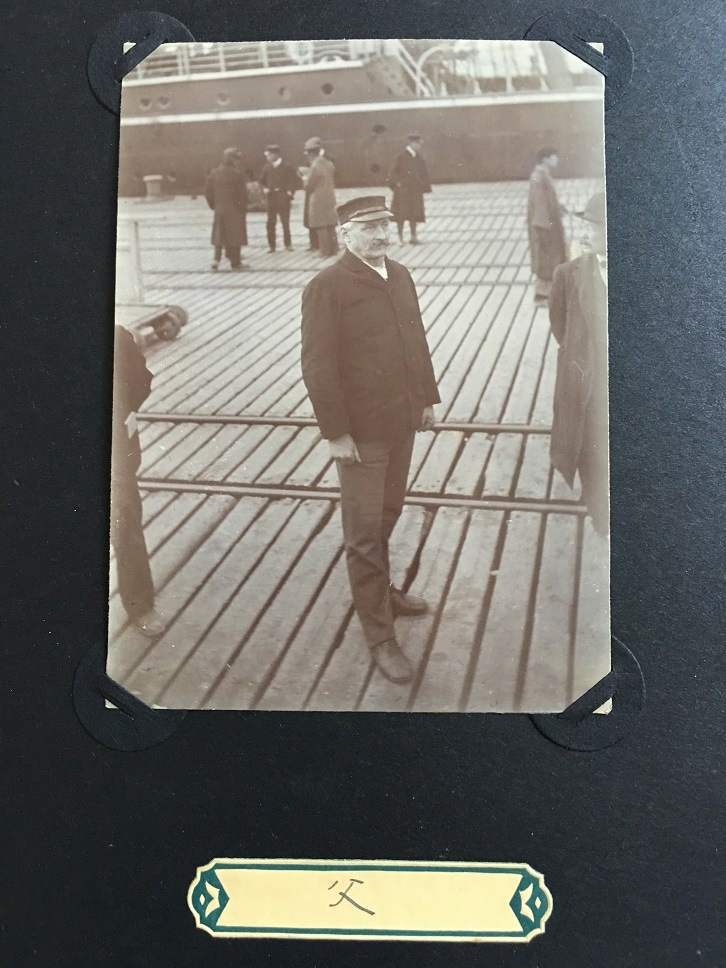

Then something else slipped into place. When the Japanese version of my book came out, Joji Tsunoda reached out to me and showed me an amazing collection of five or six large photo albums packed with photographs by his father, Ranso Wolff, who had worked for Helm Brothers for two decades. Those pictures included many of Helm Brothers operations, and had been taken over a thirty-year period between 1910 and 1945. I have written about his remarkable story on this blog before. Joji told me of a story he heard from his uncle, Ranso’s brother-in-law. Shortly before Ranso married, Joji’s uncle, Ranso’s future brother-in-law, was walking past the dock when he heard a large Danish gentleman shouting orders at his workers.

The former Danish captain, Charles Wolff (1848-1920,) was Ranso’s father, who also worked for Helm Brothers. Joji’s uncle went home and told his sister, who was engaged to be married to Ranso that she was about to marry the son of a devil. At the time, seeing the picture above, which appears to be taken at Yokohama’s South Pier, I had assumed that Wolf was managing Helm Brothers’ stevedoring operations at Yokohama harbor, but Joji later told me that his grandfather had been manager of Helm Dock, and that the family had once lived in housing built for workers at the Docks. And as I was going through Joji’s father’s treasure trove of Yokohama pictures, I came across one taken about 1919 that I thought could be a picture of the Helm Dock operations.

Now I was truly curious. I went through records of properties in Yokohama that the Helms had once owned. On the list was a very large property at 200 Takegashira, Negishi. That must be it, I thought. On this day, Japan was playing the United States in the World Baseball Classic. Everyone’s eyes would be glued to their television sets. It would be a good day to explore. I took the train to Negishi Station and asked a policeman for directions. “Go to the river then turn right before crossing the bridge,” he said. He warned me that Takegashira was on the other side of the river, but that there was no sidewalk on either side of the road along the canal where traffic was heavy.

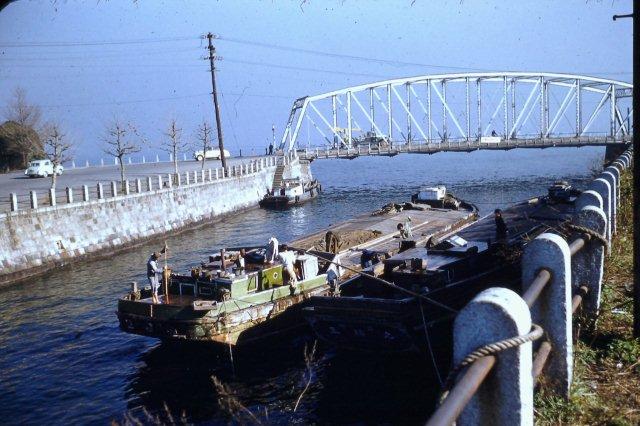

Carrying my large boxes of sembe I walked along that wide, heavily trafficked road until I finally reached the river and turned right just before the river as the policeman had recommended. I walked along the river, checking each bridge for signs that might say Helm Dock. I passed five bridges and had no luck. As I approached the sixth bridge, I looked across what the policeman had described as a river, but I now realized, was more like a canal. This is what I saw.

There was a tiny bridge, crossing an empty space from which descended a stone ramp–what could well be the ramp the shipbuilding operation at Helm Dock had used to launch new ships. I crossed the canal, and walked along the anal-side of the bridge looking for a Helm Dock sign. There was none. Meanwhile, big trucks were speeding past -one came so close the wind buffeted me against the railing. I gave up on my search for the plaque. Why would they put a plaque such a dangerous place anyway! I crossed to the other side of the road and found a side entrance to the six-story building that sat behind the bridge. When I saw a lady with a bag of groceries headed for the apartment building, I excused myself profusely and asked her if she knew anything about where Helm Dock was. “That’s it right there,” she said, pointing to the narrow space between the apartment building and the tiny bridge. The apartment building had been built right on top of the ship-building site, and the builders hadn’t bothered to remove the stone ramp. When I tried to ask more questions, the lady shook her head and rushed towards the apartment: “The final game of the World Baseball Classic is about to start.” I nodded my head. I understood. That tournament was all anybody had been talking about since I had arrived in Japan several weeks before.

The streets were empty and I had nobody else to ask. I didn’t know how to get to the hilltop park the sembe lady had recommended so instead I took a bus to Sankeien, a beautiful garden park in the neighborhood that is also famous for its cherry blossoms. My family had once summered on a hill nearby overlooking the ocean. I still have a cousin who lives nearby on what locals sometimes still call Helm Hill, although the nearby ocean has long since been filled in for miles around. I was hungry so I went into a nearby soba shop to order a bowl of noodles. I ate as I watched the baseball game on television. Suddenly the shop exploded into cheers. The patrons were celebrating Japan’s victory over the United States. Batting and pitching star Ohtani had come in as a relief pitcher in the final inning to strike out his Angels teammate. A dramatic end to the tournament. The old men in the soba shop chattered as the broadcast station began replaying the highlights of the game. “Japan is not doing so well these days but at least we are at the top of the world in baseball,” said one old man. You know, it’s not well known, but Ohtani’s father worked at a Mitsubishi Heavy factory around here. Spread the word. He’s really one of ours.”

I was happy for these men were adopting Ohtani as a local boy. Three decades of deflation had left Japan’s economy weak; salaries had hardly budged for thirty years, and after spending billions of dollars on the Tokyo Olympics, COVID had made it impossible for spectators to visit the Olympics. Now, finally, Japan had something to celebrate. Meanwhile, I was pleased by my own little discovery. In spite of the Helm family’s more than 100 years in Japan, almost nothing remains today of the Helm Brothers company that once had offices all across Japan. Now, here was a little ramp in stone that had lasted for more than a century and would remain for many years to come. As I looked at another photo Ranso had taken, I realized the stunning picture, complete with a streetcar crossing the bridge, had been taken from inside the Helm Docks, the Helm Brothers shipyard that Ranso’s father had managed.